As we roll through September, the most active part of hurricane season, the U.S. has already seen Hurricane Florence sweep through the southeast, bringing extensive rain, wind, and damage.

Along with much of the residential and urban land destruction, hurricanes are devastating to places that provide outdoor recreation, often leading to years-long repair efforts and even permanent closures. With this in mind, we look back at how the most destructive hurricane in U.S. history changed parks, campgrounds, and other wild places in Hurricane Katrina’s affected areas.

Camping in Hurricane Katrina’s Affected Areas, 13 Years Later

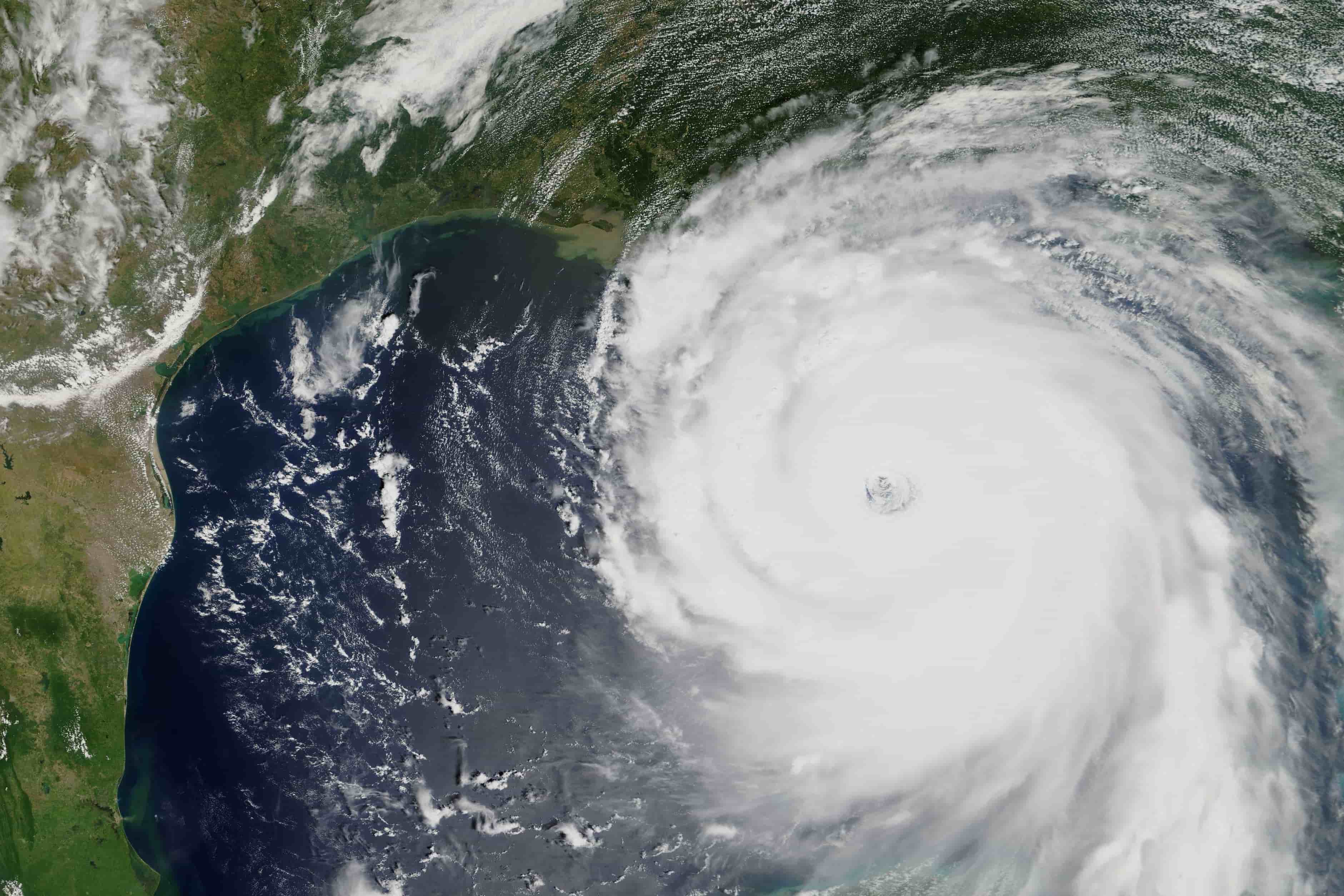

Satellite view of Hurricane Katrina approaching landfall, 2005

From August 29 until August 31, 2005, Hurricane Katrina rampaged Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, bringing with it winds of up to 140 mph. The storm surge spread across 400 miles of the Southeast region of the United States, causing rising sea levels and leaving thousands of people struggling to stay alive as they sought shelter. The storm surge and rising seal levels caused more than $100 billion dollars in damage. By August 31, 80 percent of New Orleans was flooded.

For weeks after the storm, Hurricane Katrina’s affected areas dominated news coverage, with stories coming out of New Orleans and its Lower Ninth Ward (the hardest-hit area) of levee breaks, massive flooding and rooftop rescues. When all was said and done, Katrina killed almost 2,000 people and damaged 90,000 square miles of the United States.

A shrimp boat washed ashore in Louisiana, part of the devastation of Hurricane Katrina

In 2005, it was a “one-two punch,” as Gene Reynolds, assistant secretary for the office of state parks in Louisiana, put it. Three weeks after locals in Hurricane Katrina’s affected areas began their recovery efforts, Rita hit, spreading wide across southern Louisiana. All of the parks and communities were hit pretty hard.

“Most everything below I-10 was either damaged heavily or completely destroyed,” said Reynolds. “So, you had to completely revamp. People trying to get their lives back together took precedence over trying to get the parks back up and going.”

Entire island communities and beach ecosystems had to be repaired, too. Katrina caused a considerable amount of beach erosion on islands in the Gulf, such as Dauphin Island, where sand from the beaches there were carried into the Mississippi Sound, pushing the island toward land. And 217 square miles of the Chandeleur Islands – still recovering from Hurricane Ivan the year before – were enveloped in water by Katrina and Rita, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Docks damaged after Hurricane Katrina

Campgrounds as Evacuee Shelters

The Davis Bayou Campground – part of the Gulf Islands National Seashore in Mississippi – didn’t sustain as much damage as many of Hurricane Katrina’s affected areas, since its utilities run underground. For that reason, the Federal Emergency Management Agency brought camping trailers into the campground to house victims from the hurricane.

Today, Davis Bayou Campground remains a popular destination for campers.

“It was great to visit this hidden gem again and I was pleasantly surprised at what great shape it was in following Hurricane Irma and other tropical storms last year,” writes The Dyrt camper Sarah C. “We visited in late November/early December so the bugs weren’t too bad at all. We did experience an incredible line of thunderstorms but managed to get some exploring in before the weather moved in.”

These days, campgrounds are a reliable method for providing emergency housing to residents forced out by the storm. Many Hurricane Florence evacuees found shelter in the Georgia State Parks system. “Campsites and cottages are still available and ‘dry camping’ outside of normal camping areas is available for no charge,” reads the Georgia state park website.

Rebuilding Wild Places and Recreation

Hurricane Katrina’s affected areas included 16 National Wildlife Refuges that were forced to close. Breton National Wildlife Refuge in Louisiana lost half its area during the storm, affecting the habitats of sea turtles, Mississippi sandhill cranes, Red-cockaded woodpeckers and Alabama beach mice. The Gulf Coast also lost a massive number of trees, especially in Louisiana’s Pearl River Basin and within the bottomland hardwood forests.

On the island of Grand Isle, Louisiana, recovery was quick after Katrina, according to local news outlet Houma Today. Around 400 homes were destroyed on the island, a popular destination for fishing and other wildlife gaming. Because the economy relies on tourism so heavily, the town of about 1,500 residents knew they had to rebuild quickly.

Within Grand Isle State Park – which is where the majority of camping is done on the island – staff buildings, bunks, walking trails and forests were damaged but have since been fully repaired. Also, many trees that were destroyed during the hurricane have been replanted.

Shortly after Katrina roared in, FEMA gave the city $900,000 to fix its historic fishing pier, and another $750,000 grant was used to better protect the island’s north end from floodwaters, as well as to replace beach sand that was blown away during the storm.

A severely damaged forest, two years after Hurricane Katrina

One of the state parks hit hardest by Katrina was Waveland, Mississippi’s Buccaneer State Park. The damage was intense enough to warrant documentation of the destruction and the subsequent reconstruction efforts that have taken place over the years. When winds of more than 160 mph and a tidal surge of almost 30 feet destroyed all of Buccaneer State Park’s structures, waterpark, and support facilities, according to the site the park went under varying stages of repair efforts over eight years, with the final phase completed in November of 2013.

The Challenge Continues

For the most part, Louisiana’s state parks and campgrounds recovered from Katrina within a few years, according to Reynolds.

But then there was Hurricane Gustav in 2008, which caused 48 deaths in the state, power outages for 1.5 million people and numerous trees downed by tornadoes spawned by the storm. Thirty-four parishes were declared disaster areas. Gustav was the second-most destructive storm of the 2008 Atlantic hurricane season with $8.31 billion worth of damage in all affected areas.

And it hasn’t been just hurricanes. Other natural disasters that haven’t made national news happen quite frequently in this region, according to Reynolds.

Water level approaching the road during a storm in South Louisiana. This road crosses Pointe Aux Chenes Wildlife Management Area

During the first week of March in 2016, record flooding occurred in nine locations, including Bayou Dorcheat at Lake Bistineau, Louisiana. “We had, it’s called a mesoscale convective system, which is a meteorological term,” said Reynolds. “A group of storms just sat over one area here near Baton Rouge. It just rained 18 to 20 inches…and so when that happened, you had rivers and bayous and lakes that came up, not inches but feet, in a very short amount of time, and damaged quite a few places.”

With so much natural destruction, along with recent budget cuts and layoffs, park maintenance isn’t just ongoing — it’s often behind, according to Reynolds.

“Since 2005 with all the disasters that have happened in various parts of the state, we’ve gone from cleaning up from one thing to another to another to another,” said Reynolds. “And so finally this summer we have gotten back to a point where we’re going to be reopening at least three parks that were partially closed. We’re optimistic that if we don’t get hit this time that we will finally have our head above water…”

Reynolds mentioned he was talking to a coworker just this morning about a potential storm hitting the Gulf, off the coast of Louisiana that upcoming week. “We just wish that we had one year where we can actually catch up,” he says.

Related Campgrounds:

- Piney Grove Campground, New Site, MS

Popular Articles:

Articles on The Dyrt Magazine may contain links to affiliate websites. The Dyrt receives an affiliate commission for any purchases made by using such links at no additional cost to you the consumer.