This article was brought to you by Primus, the makers of camping cookstoves that are reliable and easy to use even in the remote backcountry, high altitudes, and the farthest-flung destinations.

Over the past twenty years, scientists have observed a startling shift that’s making it trickier for everyone from hikers on the trail to the U.S. Department of Defense to find their way. Magnetic North— the direction your compass is designed to point to—is suddenly moving around as much as 25 feet a year, a variation which can lead hikers as much as a quarter mile off course.

That might not sound like much, but consider the fate of Geraldine “Gerry” Largay, the 66-year-old thru-hiker who, after going missing for over a year, was found dead just about a quarter mile from an access road that would have gotten her back onto the Appalachian Trail and to safety.

Researchers are still trying to sort out why magnetic north is wandering around like the hikers its supposed to guide. But one thing’s for sure— knowing a full range of navigational skills, including how to read a topographic map, will help you stay on course no matter what the earth’s electromagnetic field, or the weather, or the terrain, is up to.

How to Read a Topographic Map

Before getting into the technical knowledge of how to read a topographic map, here’s a little history. Topographic maps were invented by a man named John Wesley Powell, a Union army veteran and geologist who in 1884 convinced Congress to authorize a painstaking cartography project in which Powell’s team would systematically create topographic maps to better understand the resource potential and hydrology of the western landscape.

It was a tall order. Surveyors had to do much of the measurement work by hand, using aneroid barometers to calculate altitude, as well as steel tape measures and compass traverses for spatial distances. The contours of the land, based on measurements collected by surveyors, were etched into huge sheets of copper that could later be used to print and reprint the first topographic maps. And all that heavy equipment had to be trekked into the backcountry by mule.

Powell’s topographic map project was a huge, ambitious undertaking. But the payoff wasn’t only for the federal government planning out how to use resources, or geologists in search of minerals. It was also for outdoor enthusiasts to navigate more safely and confidently when armed with the knowledge of how to read a topographic map.

Understanding Scale on a Topographic Map

A topographic map can be easy to read once you know the details. First, look for the map’s scale, which will let you know how much detail the map contains. The scale on any topographic map will tell you how many miles, or fractions of a mile, one inch represents. The smaller the scale, the more detail the map has.

The larger the scale, the less detail is represented on paper. A topographic map of the whole United States, for example, may be several feet in length and width, but not contain nearly the navigable information that a pocket-sized map of just Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina might.

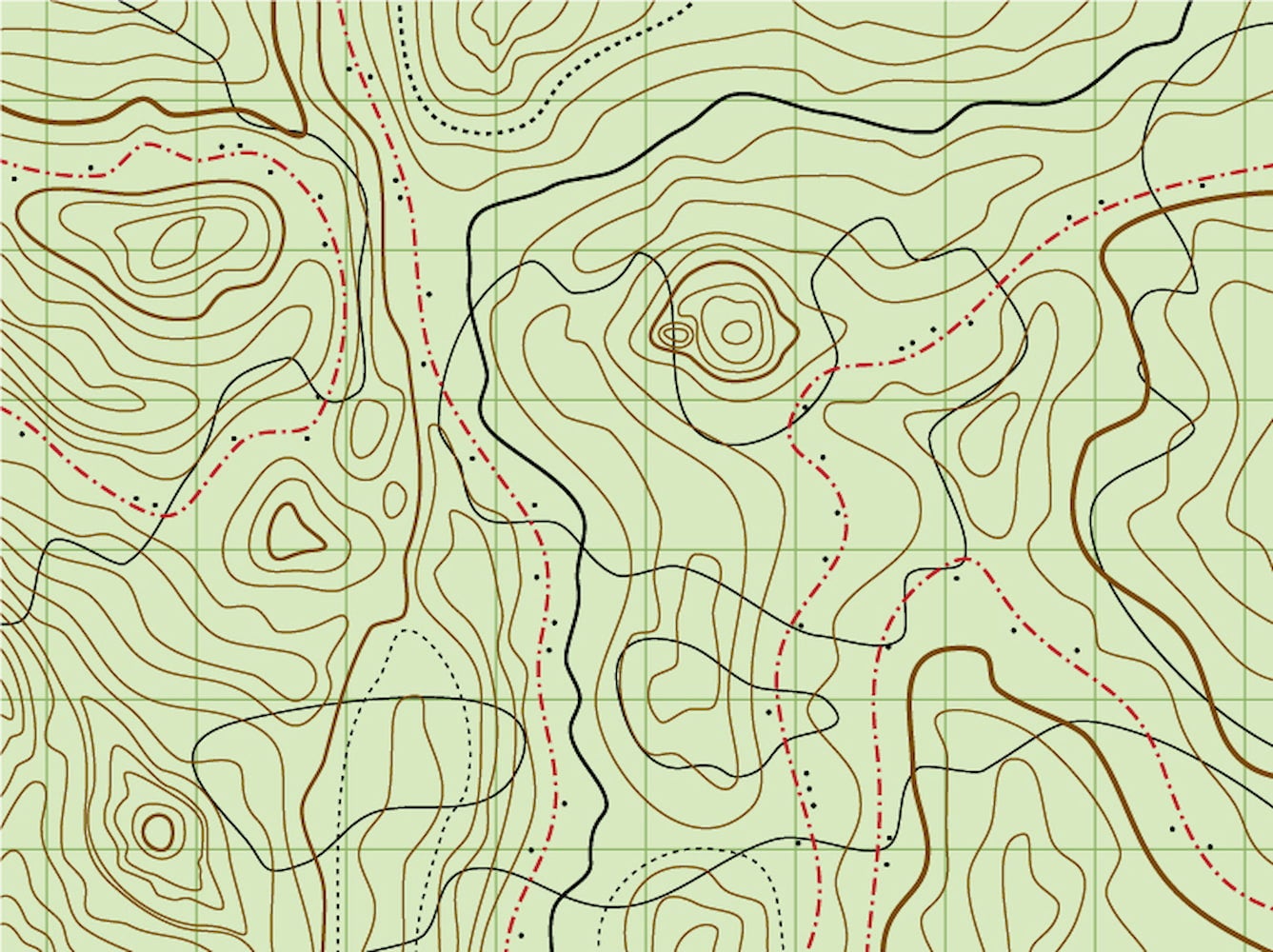

Once you know the scale represented on your map, you can start to take in the other information. The legend of a topographical map, like on any other type of map, will let you know what symbols, colors, and different types of lines represent, from rivers and roads to campgrounds, sno-parks, and waterfalls. The legend will also include other data you need to properly read a topographic map and use it to navigate.

How to Read Contour Lines On a Topographic Map

Take special note of the contour- and index-line intervals and magnetic declination. These details are essential to reading your map correctly. The contours on your topographic map show you where on the landscape elevation changes occur, and the contour interval tells you how big a change is represented between contour lines on the map. For example, a map with a contour index of 20 feet will show elevation changes in 20 foot increments.

Not only does a topographic map indicate where elevation changes occur in the landscape, it will also tell you how steep or graduate those changes will be. If a map with a 20 foot contour index illustrates a landmass with a series of ten tightly spaced concentric lines, you can expect that 200 foot elevation gain to occur more rapidly than ten contour lines of the same scale being drawn over a broad area of the map.

Noting how the contour lines are spaced out is also helpful for determining where peaks, saddles, gorges, ravines, ridgelines, and cliffs are located, and what it might be like trying to navigate that terraine. It’s a good way to estimate if a particular hike or backpacking route is safely within your technical skills.

In addition to those main contour lines— which are usually bolder than others on the map, and are called index lines— you may also find supplementary contour lines on your map that show smaller increments of elevation gain for added detail. That, combined with features from the legend like rivers, creeks, and streams can help you see where valleys have been carved by moving water over thousands of years, or where you might instead find dry washes that could be dangerous in flash floods.

How to Use Magnetic Declination on a Topographic Map

The other feature that makes topographic maps especially handy for hikers is magnetic declination. This is how you can adjust for variances between true north and magnetic north that can lead you off course. No matter how far magnetic north has separated from true north, finding magnetic declination (the angle between magnetic north and true north) can be found using the legend on your topographic map, as well as by using tools like the NOAA magnetic declination calculator.

To adjust for declination, first reference your map. If you’re east of the Mississippi River, you’ll want to adjust your declination angle in a westward direction. If you’re west of the Mississippi River, you’ll want to adjust your declination angle in an eastward direction. Think of it like the Mississippi River being “zero,” and the declination on either side as “positive” or “negative.”

Next, turn the middle of your compass according to the declination angle on your map’s legend to adjust your compass to adhere to the grid north on which your map is based, rather than magnetic north—this will keep you on trail and well-oriented, and is a major part of how to read a topographic map.

Put Your Skills To Use In the Wild

Once you know what all the parts of your topographic map and how to interpret them, you can put your skills to work in the wild. Taking a class on other wilderness skills like how to use a compass, in combination with practicing how to use a topographic map, will give you a good foundation for safely navigating the outdoors. You can even start including a topographic map of the areas you’ll be exploring in your backpacking kit, along with other essentials like your camping cookstove and extra water.

These skills aren’t only useful for deep backcountry excursions, either. A great way to use topographic maps and practice interpreting them is geocaching, a fun activity that combines navigation skills and scavenger hunts in locations around the world.

This article was brought to you by Primus.

Primus’ camping cookstove will be sure to keep your food warm no matter where you find yourself on a topographical map.

The Dyrt is the only camping app with all of the public and private campgrounds, RV parks, and free camping locations in the United States. Download now for iOS and Android.Popular Articles:

Articles on The Dyrt Magazine may contain links to affiliate websites. The Dyrt receives an affiliate commission for any purchases made by using such links at no additional cost to you the consumer.