“Is anyone not ready?”

I called out the standard question, and received silence from the four other people who stood ready to lift a patient from the snowy ground onto a backboard. It was January 2008 on the CSU Campus in Fort Collins, and I was completing my first Wilderness First Responder course.

“Lift on three. One, two, three.”

Our patient safely transported, vitals monitored and an evacuation plan drafted, we released the healthy volunteer from her insulated, immobilizing cocoon and returned to the instructor for a debrief.

Classes like Wilderness First Responder, Wilderness First Aid and Wilderness EMT are the beginning, for many, of a lifelong love of search and rescue. The high stakes, physically challenging, adrenaline-infused experience of backcountry emergencies appeals to individuals who want their adventures to mean a little more.

In a study of outdoor careers, search and rescue deserves a front-page mention.

“When you find someone and bring them home, the reaction of friends and family members, the hugs, the gratefulness, the love you feel from them . . . this why I stayed a member all these years.”

Search and Rescue is arguably the most important outdoor profession across the country. These women and men are the safety net for every hiker, climber, paddler and explorer who may fall through the cracks. They are the ones who answer the call when you are having a really bad day. Without their brave and generous support, every aspect of the outdoor recreation industry would have to seriously reconsider its business model.

Yet this profession is one comprised almost entirely of volunteers. Insurance agents, welders, librarians, new dads and local police officers are the ones who fill the ranks of most SAR teams. They complete hours of rigorous training every year and live their life on-call to help others. With very few exceptions — notably the elite Jenny Lake Rangers of Grand Teton National Park — search and rescue teams have zero full-time paid positions and survive on donations of time, gear and money from local organizations and the grateful families of those whose lives they saved.

While many search and rescue groups do not have the time to respond to multiple media inquiries, due to the high level of interest in their dramatic profession and, again, their lack of full-time personnel, I’ve compiled the perspectives of a few professionals on what it is really like to work in search and rescue.

How Did You Get your Start in Search and Rescue?

“I have worked on the White River National Forest since 1993 and spent almost every summer in the woods in Garfield County and the surrounding area. I am well trained in map, compass and GPS use. I use snowmobiles, ATVs, UTVs and 4×4 vehicles at work. Once I realized it was NOT a requirement to have EMT credentials to be a member of Search and Rescue, I wanted to join. I have knowledge and skills that can be put to use and allow me to be a contributing member of Search and Rescue while being able to spend time outside with others who enjoy the outdoors. I believe I have been lucky in health and career and I feel indebted for this. Being a member of the SAR team is the perfect opportunity for me to give back to other people in my community.”

– Kim Potter (Member of Garfield County Search and Rescue since 2015)

“While deployed to Afghanistan as a MEDEVAC crew chief, the reports say I helped save nearly 100 lives. It feels as if I lost that many, too. Three weeks from the end of the deployment, I myself was medevac’d out of the country, spending six weeks in ICU and 9 months in the hospital overall. During that time, one of our helicopters was shot down, killing the entire crew. Despite my injuries what bothered me the most was that I didn’t finish my tour of duty. Garfield County SAR is my way of completing the deployment.”

– (Prefers to remain anonymous )

“When you find someone and bring them home, the reaction of friends and family members, the hugs, the gratefulness, the love you feel from them . . . this why I stayed a member all these years.” – Bob Smith, Member of Garfield County Search and Rescue for 25 years

What is one of your most memorable rescues?

Image from nps.gov

“What turned me (on to Search and Rescue) completely, so to speak, was a plane crash on Valentine’s Day in the 80s where all four people on a mercy flight from Grand Junction to Denver survived. That gave me hope that any one of our searches after that could end happily. That day had to be one of the best days of my entire life and still is. With every search or downed aircraft after that, there was a renewed hope that it could end well for everyone.”

– Bob Smith, Member of Garfield County Search and Rescue for 25 years

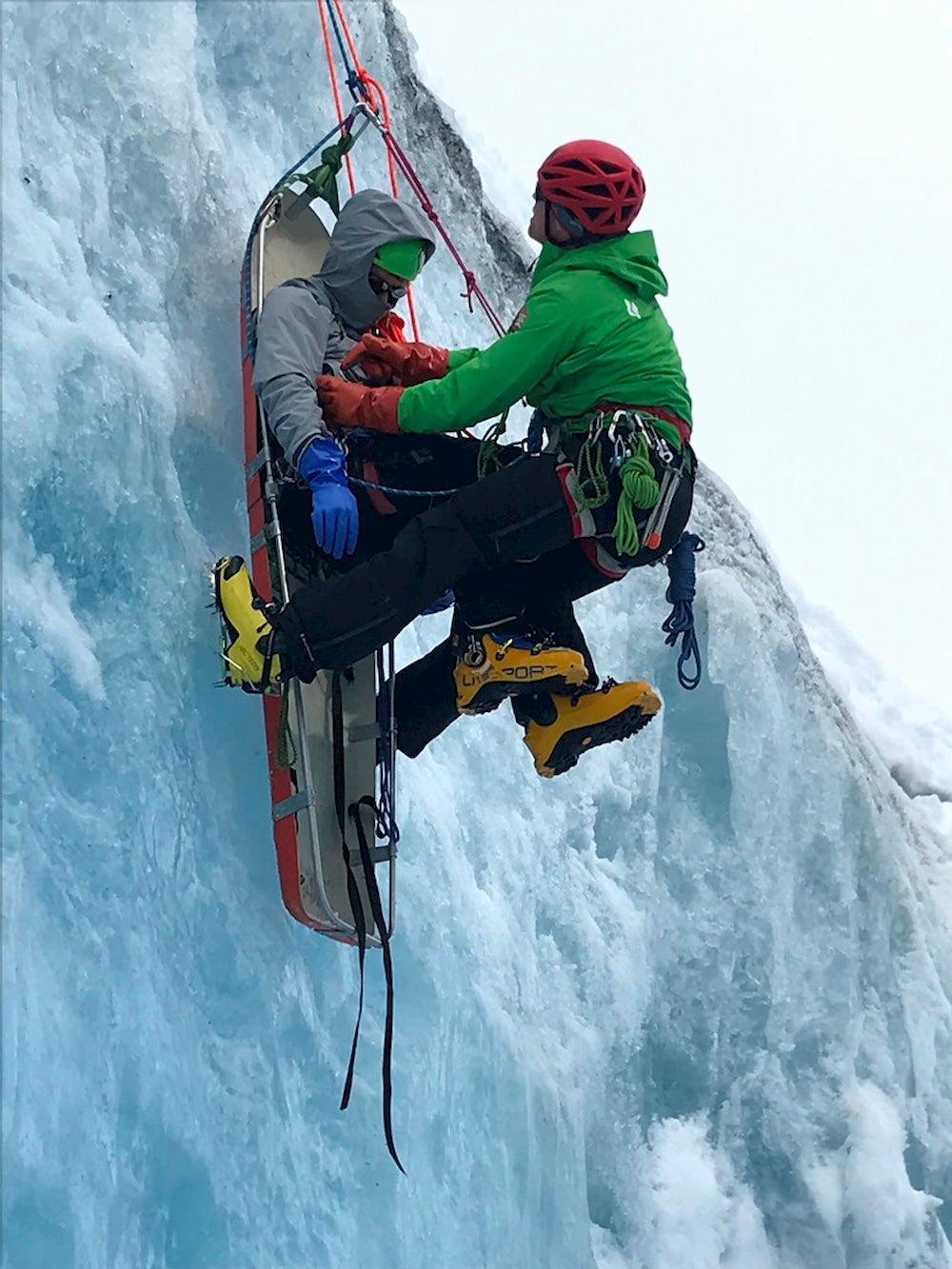

“July 21, 2010. The call came in just after noon. Lightning struck the Grand Teton multiple times, injuring 17 climbers in three parties high on the mountain. The Jenny Lake Rangers were paged, and the largest rescue operation in Teton history began. Rangers rescued 16 people from above 13,000 feet within eight hours, all suffering from various degrees of burns and lightning injuries. The extensive technical and medical expertise of the Jenny Lake Rangers enabled smooth rescue operations, and prevented further tragedy.”

– Excerpt from Jenny Lake Rangers homepage

What are the most important skills for someone considering a career in search and rescue?

“You have to develop kind of compartmentalized way of dealing with rescues, otherwise you go insane. You can’t have a whole lot of empathy, otherwise you can’t do your job. I have a hard time doing rescues now (after getting High Altitude Pulmonary Edema in Bhutan in 2013) because I know what it’s like to feel so desperate and rely on people when you can’t save yourself.” – Landen Dead, 30 year member of Mountain Rescue Aspen

“You can’t have a whole lot of empathy, otherwise you can’t do your job.”

“A willingness to give. My team needs me. When an SAR call goes out, we rely on each other to step up and be ready to respond. I feel duty bound to help as much as my family and personal life allows. Occasionally stretching those allowances to uncomfortable limits. Our community needs us. Our Counties First Responders (Fire and Law Enforcement) need to stay in town to handle emergencies, fires, accidents in town. They should be able to count on us to handle the back country incidents.” – Tom Ice, Director of Garfield County Search and Rescue, 16 years

What Do Search and Rescue Teams Wish More People Knew?

“People can call for help, any time. We never want people to think that their situation is not big enough to warrant a rescue. It’s better to make the call and get help than wait and make the situation even worse.” – Casey DeFrates, Snowmass Ski Patrol, 7 years

Another common recommendation I found on websites and public statements from Search and Rescue groups across the country is to prepare more than you think is necessary. Many people today get the idea for adventures from their favorite Instagram or Pinterest posts, with stunning views and stories of personal challenge and success. The reality is that many of these places are remote and wild, and social media doesn’t tell you about the preparation that went into that excursion before the photo was taken. Weather can change very quickly, paths can become faint or confusing, and cell phones are totally unreliable.

More research is good, but hiking with someone who has experience is better. One way that Mountain Rescue Aspen seeks to address this knowledge/experience gap is by offering workshops and clinics with mountain skills, from basic to advanced. People visiting their home town of Aspen and the Elk Mountains are in some of the most extreme terrains in the country, so learning skills like navigation and basic first aid can and does save lives.

Tom Ice, Director of Garfield County Search and Rescue, sums it up like this: Somebody needs help. Most reasonable people do not take calling SAR lightly. When they do call, they should be able to rest assured that a qualified team will be in route to help them.

The Dyrt is the only camping app with all of the public and private campgrounds, RV parks, and free camping locations in the United States. Download now for iOS and Android.Popular Articles:

Articles on The Dyrt Magazine may contain links to affiliate websites. The Dyrt receives an affiliate commission for any purchases made by using such links at no additional cost to you the consumer.